Article for the Swiss Design Awards, 2020.

Time and the Essence

Many design projects are the result of a long-term effort. They broadly fall into one of two categories. On the one hand, there are significant projects realised over extended periods of development. On the other, there are series of commissions for the same client or on a similar topic over a number of years. Both categories come with their challenges. The former can test designers’ ability to sustain their focus and energy, keep the flame alive or adapt to changes in trends and techniques. The latter confronts them with the need to reinvent themselves, the risk of creative inertia, and a potential impact on their portfolio and client list. However, these long-term projects also allow designers to develop and refine an language that is distinctively their own.

A logo — printed on a fortune cookie — that I immediately associate with a Celtic festival in my hometown (wrongly, it turns out). Another which reminds me of a childhood cartoon, though I cannot pinpoint which one. Amorphous watery blobs that shimmer to life as I play with a lenticular bookmark. There is even the typeface from the Compact Disc logo superimposed on a crawling text, itself channelling the famous Star Wars opening. These few examples demonstrate the breadth of ideas explored in the visual identity of the Bad Bonn Kilbi, a music festival which specialises in alternative rock (experimental, noise and other avant-garde genres). Its graphic designers, Adeline Mollard and Katharina Reidy, developed it over 12 years and as many concepts.

Best of Bad Bonn Kilbi, Fortune Cookies 2017© Adeline Mollard + Katharina Reidy

It seems like some things do get better with time. I am not looking back nostalgically to a distant past or a so-called golden era for design, but thinking instead about projects and commissions in which duration plays a particular role. Many of these are exceptions to the one-off model that makes up most designers’ work. Some stem from a fruitful client-designer relationship that evolves into a regular collaboration, while others exist thanks to three-year contracts. But there are also projects that have cycles built at their core, such as fashion collections or publications with a defined number of issues. Finally, there are also projects that develop out of a designer’s personal interest and can span several years.

Visual programmes

Looking back over Mollard and Reidy’s proposals for the Kilbi, it is evident that the two designers gradually turned up the dial on experimentation. Granted, the client’s openness was also crucial to these innovative identities. Although it is a very successful festival, the Kilbi does not take itself too seriously. The designers explain that “sponsors’ wishes, ticket sales or the order of the headliners — central demands for many clients — are secondary or at least do not control the design process.” Thanks to this leeway, they were able to progressively develop identities that pushed the limit a bit further every year. Mollard and Reidy can use their ongoing commission as a stylistic exercise. The commission is transformed into a research platform, which lets them develop a series of experiments as a result of the long-term commitment of the client.

“From the beginning, the designers imagined the identity as an ensemble of tools and processes.”

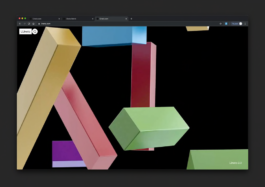

Eurostandard, “Self Identities”, les Urbaines 2019 © Eurostandard

The work of graphic design collective Eurostandard for pioneering cultural festival Les Urbaines seems to confirm the experimentation allowed by serial projects. In their three consecutive commissions for the festival, Ali-Eddine Abdelkhalek, Pierrick Brégeon and Clément Rouzaud created a visual programme on the theme of technology. From the beginning, the designers imagined the identity as an ensemble of tools and processes that would shape new images from the festival’s source material. The idea was to reflect Les Urbaines’ hybrid curatorial vision and readiness to take risks in programming emerging arts. The aim was for the identity to work as a series of “altered selfies”. These modes of representation directly echoed the questions on gender and inclusivity raised by the festival. Quite legitimately, the identity is considered as an artistic contribution to the festival’s line-up.

“The fashion industry has always pulsed to a particular frequency, but the rhythm has recently accelerated to breakneck speed.”

Seasons and episodes

Fashion exists in cycles. The industry has always pulsed to a particular frequency, but the rhythm has recently accelerated to breakneck speed. Writing in 1937, fashion historian James Laver tried to make sense of these lifecycles. He estimated that it took 50 years for something to come back in style. In the 2000s, conventional wisdom had it that these cycles were closer to 20 years. Today, the life of certain cycles can be counted in single digits. Seasons have got shorter as well: from two per year, the industry seems to have gone up to 52. Many designers hold conflicting views on this system, which appears at odds with the current geopolitical climate. Rafael Kouto is one of them, and his work offers a different take on seriality. The title of his collection, “Wishing This World Will Last Forever”, already implies that things will not continue as they are. The title sounds even more ominous today, though it originally referred to broader issues, such as the instability brought by insecurity, global heating and political changes. Kouto works by upcycling textile waste and deadstock into new pieces. In his collection, he wonders how it might be possible to prolong a period of prosperity in a world whose natural cycles have been broken. His answer lies in the introduction of another type of cycle: the circular economy.

Rafael Kouto, Wishing This World Will Last Foreverphoto © Jean-Vincent Simonet

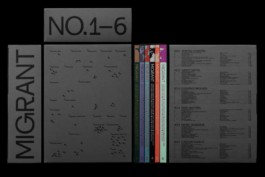

Migrant Journal © Migrant

Limited-episode runs are sometimes the best way to ensure a good season. From the onset, Migrant Journal set out to publish six issues of their magazine. This clearly defined series was vital for three reasons. It ensured the team would have enough time and space to explore the theme of migration while forcing it to publish twice yearly, thus keeping the contributions fresh. It also created a snowball effect, with each issue attracting more readers and contributors — an advantage that a single book cannot replicate. And finally, the limit was also a pragmatic way of ensuring that the steam would not run out in a never-ending project. In a world of endless sequels, their commitment to a limited run offers a welcome respite.

“Limited-episode runs are sometimes the best way to ensure a good season.”

Millions of milliseconds

On the other hand, some projects cannot have such a clear endpoint. This is often the case for photographers when they work on a series. From an initial scale counted in milliseconds — that of their shutter speed — they develop projects that can produce thousands of images spanning several years. For example, Tomas Wüthrich has been working on a series with the Penan people in Borneo since 2014. Although he has now published a book, his presentation hints at the fact that this is an ongoing project. His work is also intimately connected with the different scales of time. By examining the impact of modernity on the Penan’s daily life, Wüthrich has to reframe a historical background that goes back to the 1950s. The project is entangled in their history as much as their desires for the future.

Tomas Wüthrich, Doomed Paradise © Tomas Wüthrich

Sabina Bösch’s project also collides the instant with historical narratives. Her photography project examines a development in Swiss wrestling that has not yet gained a mainstream following. The sport has been a staple of Alpine culture since at least the 17th century and was traditionally a male-only affair. However, female interest in the sport has long existed, and the first women’s wrestling tournament in 1980 was a great success, with 15,000 spectators. Nevertheless, women wrestlers still fight for recognition. They are criticised by traditionalists and are even refused participation in the same arena as men during the “Eidgenössische”, the national tournament. Bösch followed the women’s wrestling team over a season. Her images convey the high energy of the sport: sawdust flies, faces warp and bodies contort. By framing the photographs in a way that focuses away from gender, Bösch simultaneously captures the instant and claims a place for these athletes in the sport’s long history.

Of course, long-term projects also come with their challenges. They can last forever when you work as your own client. The reason so many graphic designers have a temporary website (if they have one at all) is that for them, the project never feels ready to be published. It is a little bit easier when working for someone else, though when designers hire other designers, commissions can take a lot longer than planned. Jonathan Hares, who designed Lineto’s new website, worked on it for two years before it was launched and he is still fine-tuning it today. Commissions in defined cycles confront designers with a need for reinvention. They can also lead them to be categorised in a small niche of experimental designers, which could have an impact on future clients. As for independent projects, long-term work can also test designers’ ability to sustain their focus and energy, to keep the flame alive or to adapt to changes in trends and techniques. But overall, even though they are time-consuming, lasting projects are often the most important. They allow designers to develop and refine an idiosyncratic language which often leads to the most interesting outputs. Long-term projects also remind us that for designers to do their job well, they need to be part of the team in charge rather than hired as subcontractors for the marketing department.

Jonathan Hares, Lineto 3.0 © Lineto