Article for the Swiss Design Awards, 2019.

Mapping design territories

It is hardly news that the scale of our world has changed radically in the last twenty years. In the 1990s, McLuhan’s global village became our reality.1 We began using the internet on a large scale and the European deregulation of air travel markets gave rise to low-cost flights. Mobility has improved to the point where it is no longer surprising to study abroad, commute across borders or keep clients you have never met in places you have never been. Still, it would be an overstatement to affirm that the influence of geography has been reduced to the point of non-existence. Even a cursory glance at the news will prove you wrong: the migration of people and goods is still held against the sometimes tragic reality of borders, tunnels or lifeboats. Unions can be made and left, but what about the movement of ideas? They do not require passporting rights and easily jump walls. So how and where do they travel? What’s the influence of locality, migration or transnationality on designers’ practices? In short, how do they live in this global village?

In this year’s selection of nominees to the Swiss Design Awards, many projects show the influence of geographies. Whether maps or territories, toponomies or topographies, the selection of projects that follow provide a glimpse of the personal terrains informing the nominees’ practices.

1. Marshall McLuhan’s idea was that electronic media would turn the world into one village thanks to the possibility for information to travel instantaneously. Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1961.

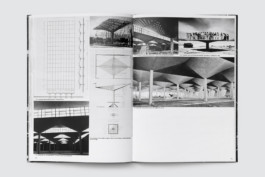

Books designed by PIN: Vierzig Jahre Gegenwart (Scheidegger & Spiess) and Space of Production (EPFL). Photograph: PIN.

Local dialects on a global scale

Although Switzerland is small, regional dialects are identifiable. Designers are not necessarily explicit about these local vocables which convey a geography that may not be determining but is discernible. A perfect example is the work of graphic designers PIN (Larissa Kasper, Samuel Bänziger and Rosario Florio). From the publications they submit to the organisation of their portfolio, PIN demonstrates a masterful programmatic method that creates a sense of architecture within the layouts. Tense margins, a structural grid and pulsating rhythms all bear the trademark of a lesser-known St Gallen tradition: the stark beauty of its book design.

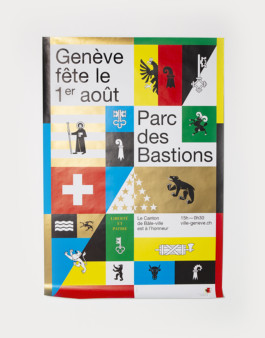

Conversely, the posters of graphic designers Neo Neo (Xavier Erni and Thuy-An Hoang) are ambassadors of the Geneva poster scene. The local accent is perceptible in the playful but relatively sober use of vernacular elements, graphics and typefaces. These elements contribute to the creation of a subtle awareness of provenance. It is far from being caricatural and may only be perceptible to the connoisseur. Still, just like PIN is firmly located in St Gallen, Neo Neo’s work is undeniably the fruit of a Genevan studio.

A poster by Neo Neo announcing the 2017 Swiss national holiday celebrations in Geneva. Photograph: Neo Neo.

Moveable feats

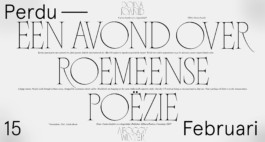

A different type of geography is perceptible in the work of nominees who go on studying outside of Switzerland. They develop undefinable accents: their work is neither fully from here nor there. A Dutch air is noticeable in the work of graphic and type designer Mateo Broillet, both in its visual language and conceptual approach. His interest in the affect of letters through their social, geographic and political constructions are the legacy of his studies at the Sandberg Instituut. “Coming to study at the Sandberg, the challenge was that the tutors were more interested in the narration surrounding the project rather than in the project itself. [To caricature], while in Switzerland people are fascinated by the technical aspect of typefaces, this is of no interest to Sandberg tutors. They see narrative potential as the source of forms rather than the other way around.”

Broillet further explains that the influence is micro rather than macrocosmic: institutions have more impact on design practices than their countries. “For instance, the MA in type design at The Hague is just as interested in the technical aspect of type design [as ECAL’s MA], while the one at Reading is more academic.” Impossible, then, to predict how Broillet’s practice would have evolved had he studied somewhere else.

A digital banner designed by Mateo Broillet using his typeface Nero Condensed. Perdu Invites: Twee Roemeense dichters, 2019.

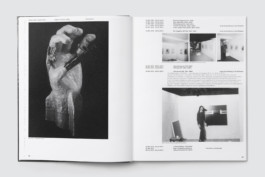

Ben Ganz’s Yale DMCA Visiting Artists poster (2017). Produced with a modified printer on aluminium plates that were then bent. Photograph: Ben Ganz.

Another example, this time with a New Haven/New York accent, is the work of graphic designer Ben Ganz. During his master’s degree at Yale, he developed a language combining his previous Swiss design education and a personal approach. His interests led to a series of posters combining innovative design devices. Ganz modified printers to control overprinting, the speed of the canvas and the material. He also bridged the gap between two and three dimensions. The first series of posters was displayed in frames reminiscent of storage shelves, while the second was made of folded aluminium sheets. Although their layout can be placed within a Swiss legacy, the striking sculptural quality of the installations demonstrates a boldness encouraged by the tradition at Yale of redefining the physicality of design artefacts.

Ben Ganz’s Yale DMCA Visiting Artists poster (2016). Produced with a modified printer and hung on a metallic structure. Photograph: Ben Ganz.

Daniel Zamarbide’s set for the piece “Direktor”. Photograph: Dylan Perrenoud.

Don’t ask where I’m from, ask where I’m a local

The physical environment is the most apparent realm of geography. Some nominees organise their work on a global scale by moving their studio abroad or collaborating across locations. For these designers, the question is not so much where they come from as where they are a local.2 How does their surroundings or travels influence their practices? The architect Daniel Zamarbide Elizondo is an example of this multi-locality. The title of his submission, Terpsichorean Geographies,3 is particularly fitting as his own career gracefully glides across locations. Working as BUREAU, the scenography nominee has offices both in Lisbon and Geneva, and the projects submitted this year span Switzerland, the US and France.

“I find myself comfortable navigating within a small diversity of places. Early on, I was ‘unrooted’ from a little and comfortable town in the Spanish Basque Country to Geneva, and now to Lisbon. Since then I have never really had a homeland, this place where you go to redefine your identity. I believe that identity does not need to be based on national criteria. It is therefore quite natural that I find myself between two different countries.”

He adds, “travelling is not exotic anymore, it has become so easy and natural. In that undefined time, I reflect, develop projects, evade, or just sleep! Although we are a small practice, we all travel a lot. The office thus becomes a space to socialise, to meet, to share, the place where we can gather together. Being based in two locations is freeing. In this context, work has developed consequently. The displacement interferes with our design process and our thinking. It is a great experience which forces you to change what you take for granted, bringing a certain form of elasticity to our thinking and our design interests.”

2. Taiye Selasi, Don’t ask where I’m from, ask where I’m a local. Lecture presented at TEDGlobal 2014 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014.

3. Terpsichore is the muse of dance.

Product designer Julie Richoz shares a similar approach to changing contexts as a way to expand her practice. She presents four projects developed in Europe, Latin America and Asia. But Richoz’s displacement is temporary, mainly through residencies and collaborations with local artisans. While she sometimes cites local vocabulary, she most often bridges regional techniques with her own creative language. Thanks to this process, she creates design objects that transcend their geographical origins.

Julie Richoz’s series of vases, Isla, was developed in the workshops of Nouvel Studio in Mexico City. Photograph: Julie Richoz.

A mock-up showing the mobile version of No Plans’ website for unu o unu, a non-profit organisation bringing together artists and special needs groups. Photograph: No Plans.

Cooperating between London and New York, No Plans (Daniel Baer and Daniel Pianetti) have developed a practice that lends itself particularly well to collaborating across an ocean. The duo of graphic designers transcends the hurdles of physicality by carving a corner of the web as their place of work. “We often get introduced to new people via our personal network, which is local to a certain degree. But we have worked with many people with whom we have never sat at the same table. The fact that our creations live on the web makes it easier for us to have a global audience.”

Asked to reflect on their relation to physical scenes, No Plans explain that “in London, the cultural sector does not have much funding. You have to learn to think commercially while protecting your integrity. New York’s situation is similar but with a more prominent role for the tech industry, whose design principles are sometimes at odds with our type of practice. [But working with the tech industry] can also bring exciting collaborations that are harder to find in Europe.”

The bus stop designed by Léo Châtelain around 1900 and transformed in 2015 into Palais—Galerie. Photograph: Prune Simon-Vermot.

Location, location, location

In the Channel 4 TV show Location, location, location, the presenters try to find the ideal home for a different set of buyers every week. Just like them, Denis Roueche and Prune Simon-Vermot (nominated in mediation) found the perfect place in Neuchâtel for their space showing design and art exhibitions. The duo transformed a bus shelter into a venue called Palais—Galerie. Before upgrading a transient waiting space to a transdisciplinary destination, the pair organised exhibitions in various locations across Western Switzerland. It is thus fitting that their activities settled down – stop on request! – in a building symbolic of commuting and travel. But the palatial venue (15m2) extends beyond physical space. It explores territories between design and art, bringing together a “constellation of singular subcultures [not yet] mapped”.4 Palais—Galerie offers not only a welcome addition to the small landscape of galleries showing art and design, but also a destination located outside of the usual circuit of design cities.

4. François Rappo, Intersection. [Palais–Galerie dossier], n.d (2018?).

5. Common-interest, Department of Non-Binaries: an exhibition about hybrid design practices and identities. [common-interest dossier], 2019.

“LLC Redux (A Great Place for Great People to Do Great Work)” by Christopher Benton, in Department of Non-Binaries, Fikra Design Biennial 01: Ministry of Graphic Design, 2018.Photograph: Kong Wen Da Gideon.

Mapping the constellation of practices

Nominated in the mediation category, common-interest (Nina Paim and Corinne Gisel) move across geographies that are not physical but concerned by methods. They have built a practice merging critical inquiry and creative storytelling to make research public. The duo uses the media they find most relevant for the situation. This includes publications, exhibitions, workshops or texts, but also pizza – for an event organised with fellow nominees depatriarchise design.

The duo presents their work as curators of an exhibition part of the Fikra Biennial in Sharjah (United Arab Emirates). Titled Ministry of Graphic Design, the biennial was organised in several departments. Common-interest developed the Department of Non-Binaries that focused on practices “blurring the categories traditionally used to delineate genres, audiences, markets and attitudes within graphic design”.5 Their curation mapped an area without defined edges that displayed the possibilities offered by designerly ways of working.

“The #Pritzker pizza (cheese = female winners).” Quite literally, a pie chart diagram showing the ratio of male to female winners of the Pritzker prize. Photograph: @ofcommoninterest

The digital platform developed by depatriarchise design to host a wide intersectional discussion on design patriarchy that amplifies female voices. Image: depatriarchise design.

Mediators depatriarchise design (Maya Ober in Basel and Anja Neidhardt in Berlin) share a similar talent for moving across territories of practice. They use formats including workshops, labs, talks, publications and a weblog to “examine the complicity of design in the reproduction of oppressive systems, focusing predominantly on patriarchy, using intersectional feminist analysis.”6 By sharing texts in a wide variety of languages, they extend the discourse beyond the usual Anglo-centric sphere. “We think the term ‘global village’ has been misinterpreted. The question of accessibility has to be posed before we state that we are all part of one. McLuhan said that ‘the world has become a computer, an electronic brain’7 – but we ask: who has access to this brain? We would like to develop different forms of knowledge production and cultural mediation. We actively use our positionalities, which means we aim to become aware of who we are, where we come from and how our thinking and acting is shaped by our identities. Nobody fits into neat categories. We aim to acknowledge these diverse realities and contexts.”

The pair explain that one field cannot be envisaged without its neighbours. “We have to think about the different layers and ‘geographies’ of a design. Since the globalisation of mass production especially, industrial design is integrated into what bell hooks names the ‘imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’.8 For instance, a majority of electronic devices consumed in the so-called Global North are assembled in Asian countries – and after their consumption disposed in African slums. But geography can also be very physical. Our latest initiative *!Labs!* takes place on a local level in Basel, and at the same time has a strong online presence.”

“Creating networks and connections between designers, researchers and activists, whether they are based in Buenos Aires, Beirut or London, brings mutual support, comprehensive exchange and immense hope”

Explaining the power lent by an online presence, depatriarchise design say that “the seam between digital and physical enables different angles of feminist work. Sara Ahmed writes that living a feminist life, and being the ‘killjoy’, can make us feel lonely.9 On the other hand, creating networks between designers, researchers and activists who share similar experiences of struggle within the design field, whether they are based in Buenos Aires, Beirut or London, brings mutual support, comprehensive exchange and immense hope.”

6. Depatriarchise design, About depatriarchise design, n.d.

7. McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy.

8. Gloria Jean Watkins, who writes under the name bell hooks, is an American author, professor and activist whose work focuses on the intersectionality of race, capitalism, gender, oppression and class domination. bell hooks, Feminism is for everybody. London: Pluto Press, 2000.

9. Sara Ahmed is an independent feminist scholar and writer who was the inaugural director of the Centre for Feminist Research at Goldsmiths University in London.

Geographies as sources and narratives

Certain designers explicitly harness the strong narratives contained in geographies. Product designer Christian Paul Kägi presents Bananatex, a collection created for his brand Qwstion. It uses a specially developed fabric made of fibres of the Abacá banana plant (Musa textilis). The collection is representative of the networks of production. Kägi developed the collection in Zurich; the Abacá is grown in the Philippines, then woven in Taiwan. The promotional series of photographs for Bananatex builds on this globality. It shows models wearing the bags in the various sites where the fibres are harvested and transformed. The narratives surrounding the research and production processes are thus part of the final object.

An image from the Qwstion campaign showing a model wearing the Bananatex backpack in front of fibres hung to dry. Photograph: Lauschicht.

A textile developed by Estelle Bourdet marrying digital sketches and traditional weaving techniques. Photograph: Moostang.

The tactile textiles developed by Marie Jambers. Photograph: Marie Jambers.

Textile designer Marie Jambers also builds on the places of production – albeit on a local scale – by using wool from an association of producers in Neuchâtel. The local sourcing of material works well with the themes explored in her work. She creates an intimate universe of shapes, colours and materials that can be touched and lived. Her textiles evoke a micro-geography down to the scale of the hand: free rein is given to experiments at the loom, producing a fabric that can be played with, dyed or assembled.

Another textile designer, Estelle Bourdet similarly builds on micro-geographies. In her dossier, she quotes The poetics of space.10 By referring to parts of a house, Bourdet bases her work on Bachelard’s use of spatial typologies as metaphors of homes for our souvenirs. Her weavings reflect the characteristics of the bedroom, the hall, the garden and so on by using colours, proportions and motifs that explore the representation of living spaces. To that microscopic examination, Bourdet adds a macroscopic dimension. Her project aims to be a social, formal and temporal recontextualization of carpet production that exists in Sweden since the 18th century.

10. Gaston Bachelard’s 1957 text discusses the potential of the poetic image as an ontological device. Its originality comes from the predominance given to imagination and poetics as a major power of human nature.

An image from the collection CH 2127 Les Bayards by Bryan Colò, who takes a satirical angle to talk about his origins. Here, the model is shot in front of the local dairy. Photograph: Cynthia Mai Amman.

Fan Pleat Denim Panel for Jacket, a piece from Eliane Heutschi’s AW18 collection, Knife Pleats, developed for her own brand [savoar fer].

Fashion designer Eliane Heutschi adds the dimension of history to geography. She found her mission while working for an NGO in Peru, where she realised the importance of perpetuating ancestral know-hows which are in the hands of a dwindling number of artisans. She decided to base the collections of her brand [savoar fer] on techniques which can often be traced to specific locations. Her AW17 collection made use of bobbin lace, which was developed in Italy and Belgium in the 15th century. SS18 referred to our mothers and grandmothers’ use of the cross stitch. Finally, AW18 used knife pleats, which originate from Scotland.

But origins, historical or autobiographical, are not always the source of peaceful inspiration. Their push-pull influence is explored in the collections of fashion designer Bryan Colò, who needed to leave his village to reassess and redefine the richness of his identity. Forced in exile to be able to live freely as a gay man, he soon found that the promised land – in his case, Geneva – was a dystopia ruled by bureaucrats. Using satire, caricature and the tradition of Carnival, Colò takes his revenge on both the village and the city. He creates a collection that alludes to power dressing (blazer, trench coat and trousers) and to sportswear, fabricating armour for him to confront demons past and present.

An image from Turunç (Bitter Orange), Solène Gün’s series exploring the lives of young male Turkish migrants in Paris and Berlin. Photograph: Solène Gün.

Also stemming from the autobiographical, the work of photographer Solène Gün addresses geography and migration. An immigrant from Turkey herself, Gün’s project deals with young male Turkish emigrants in the suburbs of Paris and Berlin. On her images, barbed wire contrasts with pigeons taking flight or a figure looking into the distance. While migration is often attempted in hope for a better world, here the destination suggests otherwise. The non-places documented by Gün convey a mundane daily life haunted by the void of displacement where the reconstruction of identity happens through the recreation of a community.

The global village square

So what have we learned on our tour of the global village square? By mapping the projects and practices of a selection of nominees, we have seen the different venues where geography exerts its influence. Sometimes, location provides merely a flavour to the work. In other instances, geography functions as a framework that organises the creative life of the studio or provides new sources of inspiration. Choosing where to situate a practice or a project, both physically and metaphorically, locates and expands the possibilities offered by design. Geographies can also be used as source material in designers’ work. In the latter examples, notions of provenance, situation or destination are determining in the process and the outcome: geography has a peritextual quality. The cartography shows that the impact of geographies is far from reductive. It both locates and expands practices. Some projects are maps, others territories. By looking at them from the angle of geography, a prismatic understanding of design is revealed.