Article for the Swiss Design Awards, 2019.

Geometries of collaboration

In popular culture, the creative process is often depicted as a lonely endeavour. But while a bereft, misunderstood genius producing a masterpiece through tears and sweat is indeed a compelling narrative, the image could not be further from reality.¹ To paraphrase Becker’s argument in Art Worlds, the designer, photographer or mediator — who we should really think of as any other type of worker — relies on extensive networks to produce the kind of labour that the applied arts world is noted for.² Whether it is to share knowledge, produce work, distribute the result of the effort or let an audience appraise it, cooperation is paramount to creation.

1. Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers, New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1965.

2. Howard S. Becker, Art Worlds, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

Needless to say, the Swiss Design Awards play a significant role in this network. They have done so for more than a century. They engage in the world of applied arts by encouraging the field through financial support, commissioning designers and promoting them. For the nominees, however, other synergies happen earlier. The most fundamental advantage of teaming up with others is that it lets us connect different skills to create work that goes further than what is achievable by a single person. This teamwork takes place at different levels, starting with joint efforts in the atelier and ranging to external cooperation with partners, suppliers and clients. How does working together impact the creative process of this year’s nominees? How do they organise to combine efforts, and what are the different qualities of collaboration?

The Midi chair developed by Micael Filipe and Romain Viricel over a year of almost daily conversation between London and Lyon. Photograph: Filipe & Viricel.

Parallelism

In its most straightforward appearance, collaboration is internal and takes place between designers within the same sphere of practice. We could schematize it by parallel lines: practitioners combine similar and often completing skills. Product designers Micael Filipe and Romain Viricel, who met at ECAL, chose to have equal roles in the design process. They both possess a similar skill set, so the particularity each person brings to the collaboration is their personal experience, taste and way of looking. Now based in London for the former and Lyon for the latter, they are nominated for the Midi Chair, which they developed over a year of almost daily conversation. And how did they share ideas? Their medium of choice is the failproof sketch, albeit in a contemporary form. “We use drawings or 3D renders as supports to share an idea; a good drawing doesn’t necessarily need an explanation. We also meet regularly in person to materialise our ideas through a physical model.”

Graphic design Studio Ard (Guillaume Chuard and Daniel Nørregaard) use a slow, organic collaborative process that also depends on visual material: a giant pinboard that acts as the receptacle for inchoate ideas. Rather than take decisions, they rely on an informal process where they stimulate each other through references and tests. At some point, one designer naturally takes responsibility for the project. The duo met at the Royal College of Art in London after studying at ECAL and the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and see their practice at the centre of a triangle defined by Swiss rationality, Dutch radicalism and English pop. To this smorgasbord of influences, they add their own preferences: Chuard is passionate about materiality while Nørregaard is enthusiastic about texts. When it comes to choosing the music in the studio, each has his taste too – though Nørregaard has the upper hand as he often arrives before Chuard in the morning. The real struggle of working together so closely begins at noon. Chuard cannot eat gluten and Nørregaard is a lactose-intolerant vegetarian, making lunch the most difficult decision of the day.

The giant pin board at the heart of Studio Ard’s creative process. Photograph: Studio Ard.

The view each partner has of the other’s studio. Photograph: No Plans.

Yet other designers never have the opportunity to break bread: they collaborate across different locations and must, therefore, rely on other systems to share ideas. The duo of graphic designers No Plans (Daniel Pianetti in New York and Daniel Baer in London) attempted splitting web design jobs at first, with one partner taking care of the design and the other coding it. However, they realised that they worked best when each took turns leading specific projects, with the other person having the role of critiquing it regularly. “We have surprisingly different personalities and design styles. We both understand and respect the other’s approach to visual design and interfaces. Interestingly, we could never replicate what the other half is doing.” With one designer in New York and the other in London, collaboration takes place across many digital platforms (Trello, Appear.in, Slack, GitHub, Google Suite and so on) to ensure constant communication.

But there's another, less corporate platform which plays a significant role for No Plans. Daniel Pianetti is one of the founders of Are.na, the collaborative tool for visual organisation. For the duo, the platform is more than a means to share ideas internally. “Are.na has a special role in our projects due to its community: as we collaborate over time with other designers, developers and clients, these connections become a resource themselves. It’s not rare to pick a collaborator’s contribution for a completely unrelated project months later, ask an old client about an event they’re researching for on the platform and enquire or even be asked for services after diving into someone’s online research.” By creating their own collaborative tool, the designers bring together online and offline communities. Furthermore, they have access to flexible partnerships. This contributes to redefining the idea of the collective.

An image from the collection “Restaurant zum Schwälbli” by Collective Swallow. Photograph: Simon Habegger.

Fashion designers Collective Swallow (Anaïs Marti and Ugo Pecoraio, who met at FNHW Basel) are also based in two different locations, Basel and Berlin. The first half of their moniker is a nod to the fact that creating a collection is always a joint effort. “There are so many more people involved than just the two of us, and we like to collaborate with other designers or artists for specific products.” Within the collective itself, each plays a specific role which evolved over time and comes from their education but also reflects group dynamics. Marti has a background in tailoring and experience as a commercial fashion designer. She is therefore in charge of developing the collection, creating the pieces and managing the production.

On the other hand, Pecoraio has experience in the PR world. His background in graphic design means he also oversees prints, look-books, labels and hangtags. “We both have our areas of expertise but working closely together is very important. In the beginning of a collection, we both research and collect inputs which we then select and structure together. We meet for a weekend in a house in the Jura and discuss and shape the new upcoming collection. There, we create the mood board and finalise the concept which then leads all following actions to the collection.” After this process, Marti takes over: she draws and develops the pieces. Along the way, there is a delicate balance between shared decisions and relying on each other’s expertise, an equilibrium which is nurtured by their relationship. Indeed, Collective Swallow stresses that their collaboration stems from friendship: “we were friends first, and then decided to build a label together.”

An excerpt from Agathe Zaerpour and Philippine Chaumont’s editorial work. Photograph: Chaumont-Zaerpour.

Perpendicularity

In a slightly different example of teamwork, nominees group together for projects which take place outside of their usual field. In these cases, collaborating is about creating perpendicular bisectors. Denis Roueche, who trained as a graphic designer, and Prune Simon-Vermot, who studied photography, teamed up to open Palais—Galerie. Quite naturally, each brought their skills to the table: Roueche designs the posters and Simon-Vermot documents the exhibitions. But the main work of a gallery – curation, which goes beyond their initial training – is shared by both equally; teamwork truly makes the dream… work.

Another example would be Agathe Zaerpour and Philippine Chaumont. They trained as graphic designers together at ECAL and increasingly worked as art directors after graduating. So far, their trajectory is not unusual. This year, however, they are applying in the photography category with projects spanning from the documentary to the self-initiated and the editorial. Their work mirrors the skills they have in the fields of both design and photography. By teaming up together, they are in a position to develop a photographic discourse that is firmly their own. Not only does it display a graphic approach – both in the composition of the images and their presentation in rhythmic layouts – but it also delivers their own voice: a self-confident, uncanny quirkiness that seeps through the subjects they choose and the treatment of their images.

Intersection

When nominees work hand in hand with clients, the partnership becomes a new space where the work can develop thanks to the convergence of needs and wants from all sides. We could schematise it by the intersection between different planes. Even further, collaboration can lead to practices that exist in the liminal space between various fields. For instance, photographer Marc Asekhame is also the publisher of a magazine, Periodico, which he edits in collaboration with graphic designer Teo Schifferli. When he is working on Periodico, Asekhame is therefore simultaneously photographer, editor, publisher and agent.

He blurs the line further by shooting personalised advertisements in close collaboration with the announcers, consequently benefitting thrice from the partnership: it brings financial support, lets him work as a photographer and hands him complete creative control over the magazine. Asekhame says: “I understand the ads in Periodico as an integral part of the content of the magazine. They become a collaboration between the institution/the brand and the publication.” But the periodical might well have the upper hand in this partnership, thanks to the clear conditions it sets. “For the last two issues, we let the advertiser appoint one person who would be portrayed by us and then, with the addition of the logo, become the advertisement.” Until now, this strategy has been successful and even seems to be convincing new clients. “So far, we have mostly worked with people who knew the magazine or my work, but now people approach us to publish and collaborate on an ad.” For a brand or institution, commissioning an ad thus becomes a way to borrow the magazine’s voice and present themselves as true partners to a cultural enterprise.

A personalised ad for fellow nominees Ottolinger shot by Marc Asekhame and published in his magazine Periodico, here before the addition of the brand’s logo.

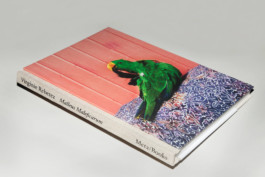

Virginie Rebetez’s book Malleus Maleficarum, which was the result of multiple layers of collaboration: with the subjects in her pictures, the publisher, the designer and finally the audience who is asked to play an active role. Photograph: Virginie Rebetez.

Another photographer, Virginie Rebetez presents work she developed as part of Fribourg’s photographic investigation. The commission is a biyearly call for projects, open to all professional photographers, that aims to support the field by selecting one project whose theme or topic concerns the canton. It is an unusual format because once the proposal is accepted, the photographer has almost complete freedom to develop their work independently over two years. Rebetez wanted to retell the story of Claude Bergier, who was accused of witchcraft and burnt in 1628, by collaborating with mediums and healers. She worked closely with them over a series of meetings and asked them to contact Bergier. To convey the story, the book and exhibition layer two voices: her work as a photographer and texts transcribing her sessions with the mediums. In the publication, it is as if she brings all the actors around the same table. The book is, therefore, a vessel gathering voices in a subtle alchemy. The object came to life through a careful joint effort with the publisher, Meta/Books, and the book designer, Chi-Long Trieu. The triad (photographer, publisher and designer) becomes tetrad when the final collaborator – the public – sits at the table. The active part played by the audience is indeed necessary to recompose the puzzle and interpret Bergier’s story.

An invitation for Christopher Raeburn’s SS13 show, Deploy, designed by Simon Palmieri and Régis Tosetti. Photograph: Sam Scott-Hunter.

The work of graphic designers Simon Palmieri and Régis Tosetti sheds light on a different type of collaboration with the client. The close relationship they have developed with fashion designer Christopher Ræburn over ten years allowed to turn a simple commission into an extraordinary partnership. The duo began by designing the brand’s logo before developing its full range of communications materials. Once trust was established, the collaboration bloomed and materialised between the needs and desires of both sides. Palmieri and Tosetti are now going beyond the usual graphic design brief by designing prints for the clothes, set designs for shows and sounds for campaigns. Thanks to this long-term relationship, the duo thus works in complete symbiosis with the client, who benefits from the collaboration as much as the designers do.

Set designer Daniel Zamarbide (working as BUREAU) goes one step further in his professional relationships. He rejects the notion of the client, avoiding the word “since the client-service relation implies a commercial rapport forcing one to comply with the other’s expectations as long as there is a monetary exchange.” Instead, he favours a collaborative dynamic within his work. Reflecting on his influences, Zamarbide cites the work of sociologist Richard Sennett, notably The Craftsman (2008) and Together (2012) as theoretical foundations. In the former, Sennett argues that we all have an innate desire to make things well; in the latter, he proposes that we need to do it in co-operation. These ideas resonate with Zamarbide, who has always needed to confront his own creative agenda and has therefore embraced working with others.

Collaboration as practice

Nominated in the mediation category, the platform depatriarchise design (currently co-run by Maya Ober and Anja Neidhardt) also fundamentally relies on working with others. They use an intersectional approach to feminism and must, therefore, collaborate with a wide range of people to build on common political ground. But rather than seeing itself as a facilitator of empowerment, the platform enlists every reader as a potential collaborator in the resistance against patriarchy. For depatriarchise design, “collaboration is based on common ground and generosity; it gives hope.” The collective resistance aims to be transparent and non-hierarchical, and the organisers hence want to take this opportunity to acknowledge the collaborators on their platform.

Photographers Yann Gross and Arguiñe Escandon rely on a delicate collaboration with the other while avoiding othering. Their project The Holes of The Tree was developed over two years and retraces the steps of Charles Kroehle, a photographer who took the first pictures in the Peruvian Amazon between 1888 and 1892. Treading carefully to avoid cultural appropriation – Kroehle was an archetypal colonial adventurer, and his images relied heavily on exoticism – Escandon and Gross set on the self-admitted impossible endeavour of striving to erase the distance of observation, and thus avoiding the use of photography as a colonial instrument of representation, by becoming subjects themselves. Their first step was to defocus their gaze by spending time in the jungle, feeding on plants and observing the indigenous communities’ relationship with their environment. They then translated their observations in images. Escandon has an emotional approach to image-making, while Gross is more methodical. These complementing aspects of their collaboration helped them to interact with each subject differently and to build a more complex representation of their experiences.

A postcard showing Charles Kroehle posing as the archetypal colonial adventurer, excerpted from The Hole in the Trees by Arguiñe Escandon and Yann Gross.

Beg to differ

Collaboration abounds. Whether through teamwork, partnership or alliance, design relies heavily on the other to deliver projects that are more accomplished or more complex than if they had been attempted independently. The actual process is separate in each case as designers have distinctive working methods: collaboration is thus always different. Because it fuses practitioners’ interests with their partners’, the process can leave a lasting trace. Furthermore, perhaps in line with our constant presence on social media, notions of collaboration with an audience have become more relevant than ever. All these aspects are parts of the reason why we strive to team up with others.

Professional cooperation has been present forever, but some aspects are unique to our times. It is clear that the profusion of digital tools facilitates nomad, fluid partnerships that form and disappear as they are needed. The mental image of the network should thus be pictured as a protean, flowing, temporary relationship. It links subcultures, beliefs and appreciation – rather than, as we might traditionally imagine it, closed old boys’ networks, contracts or predetermined exchange. At a recent conference in Bern, design writer and curator Emily King shared an insight she gained while working on a piece.³ It seems like fromagers cannot rely purely on their own cheese cultures in the long term: they have to share them with other dairies to avoid weakening bacteria. Expanding on this cheesy metaphor is somehow quite fitting for the design world. If we want to build a sustainable and sustaining design practice, we must abide by the real power of sharing, which is about the “and” rather than the “either/or”. This seems to be especially relevant this year, as we notice a number of projects dealing with social engagement such as real-world issues, gender, identity, race and power dynamics. It confirms the importance of engaging with the other. Only by seeking the difference in collaboration will we be able to make our best work, and achieve a better world.

3. Emily King, Curating and Writing Beyond Academia, conference at University of Bern, Bern, 4 April 2019; Emily King, “Leila McAlister”, in: The Gentlewoman 6, 2012.